October 3, 2025

The Rise and Fall of Tupperware: Strategic Lessons from an Iconic Brand

The Rise and Fall of Tupperware: Strategic Lessons from an Iconic Brand

Introduction

Tupperware is a classic example of an iconic brand’s rapid rise to global success and its gradual decline; its journey offers numerous strategic lessons. Tupperware was a brand recognized in almost every home in the world and, thanks to its strong trademark, was able to maintain a high-profit margin for years (a stable 66% gross profit margin over the years). The following is an overview of how Tupperware was born, grew, and what ultimately led to the company’s downfall.

The Beginning: An Innovative Product and a Sales Model Revolution

The Tupperware story began in 1946 when chemist Earl Tupper developed an innovative polyethylene plastic lid that could be sealed airtight. Initially, Tupper tried to market his products through traditional retail channels – department stores and hardware stores. However, these channels proved unsuccessful because the end consumer found it difficult to understand the correct way to use the novel lid.

The Tupperware story began in 1946 when chemist Earl Tupper developed an innovative polyethylene plastic lid that could be sealed airtight. Initially, Tupper tried to market his products through traditional retail channels – department stores and hardware stores. However, these channels proved unsuccessful because the end consumer found it difficult to understand the correct way to use the novel lid.

The breakthrough came thanks to Brownie Wise, a small business sales representative who understood that the benefits of the Tupperware product needed to be actively demonstrated to customers. In the early 1950s, Wise developed the legendary format of in-home Tupperware sales parties. These Tupperware parties were not merely sales events but social gatherings—homemakers gathered in homes to socialize and, in the process, try the plastic containers with their own hands and become convinced of their benefits. This novel direct sales strategy proved to be very successful and, at the time, offered many women a rare opportunity to earn an independent income and build a career. With low capital costs and a highly scalable sales network, it spurred powerful and community-based brand loyalty. In summary, it was not just selling—it was the application of a social network in the service of product marketing and distribution.

The results were remarkable. By 1952, Tupperware’s annual sales exceeded $2 million, and within three years of implementing the party model created by Wise, sales grew several tens of times over. By 1954, Tupperware’s revenue had already reached $25 million. Such exponential growth signified the potential of the new sales strategy—an innovative product combined with the right marketing channel turned Tupperware into the favorite brand of American homemakers in a short time.

In addition to its commercial success, the Tupperware model also had a social dimension, encouraging women toward economic independence during a period when it was not very common.

Global Growth and Going Public

Success in America quickly led to Tupperware’s international expansion. In the 1960s and 1970s, sales growth continued at an impressive pace—both revenue and profit managed to double approximately every five years. By 1976, the company’s annual revenue exceeded the $500 million mark. Tupperware products—durable, colorful, and practical storage containers—found their way into new homes around the world thanks to the direct sales network. The brand’s name recognition grew, and Tupperware became synonymous with reusable food containers.

Supported by a global sales network built over decades and a strong brand, Tupperware eventually reached the stock markets. In May 1996, Tupperware went public. In its initial public offering, the company’s market value was estimated at approximately $2.6 billion. In the same year, Tupperware was already earning over a billion dollars in annual revenue. At the end of the 1990s, the company also had an impressive sales organization: the number of independent sales consultants reached into the millions.

The Peak and the First Warning Signs

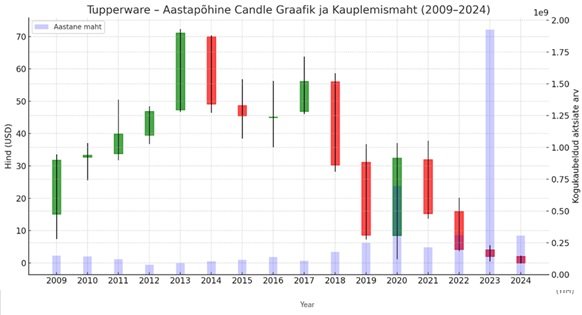

Charts 1 and 2 show how Tupperware’s financial results peaked in 2013. That same year became a historic high point for the company. Global revenue reached a record $2.67 billion that year. The stock price had undergone a long rise—by the end of 2013, Tupperware’s stock reached its all-time high, closing in December at around $72. Tupperware’s market capitalization in 2013 was $4.7 billion. Everything seemed excellent: Tupperware was a global market leader in its niche, sales and profits had grown over the decade, and investors enjoyed a generous dividend policy.

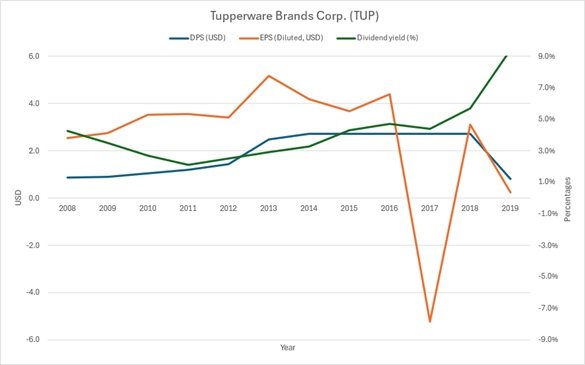

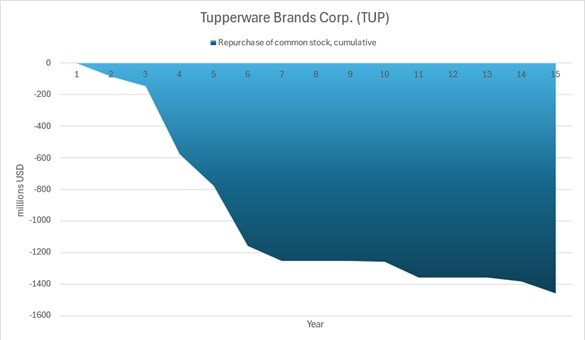

Unfortunately, hidden within this peak of success were the first troubles that hinted at potential future difficulties. One warning sign was the change in the company’s financial strategy—management began to focus more and more on extracting money from the existing business for shareholders (see Chart 4), instead of aggressively investing in future opportunities. Between 2009 and 2022, Tupperware spent $1.46 billion on stock buybacks plus dividend payments, while investments in modernizing the business model (such as developing e-commerce) remained modest. Chart 3 shows how the company paid a stable and high dividend (DPS, Dividend Yield) even as earnings (EPS) began to decline. Approximately 2-3% of shares were repurchased regularly each year. These steps showed management’s goal of keeping the stock price high by all possible means, in other words, to divert attention from the company’s existential problems.

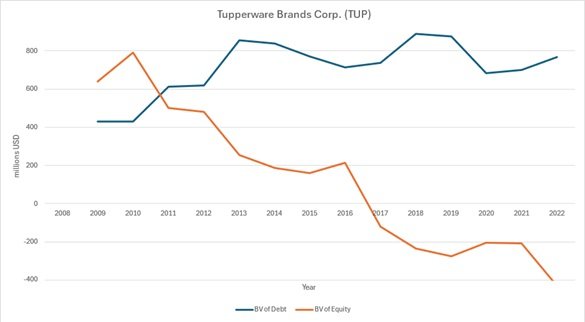

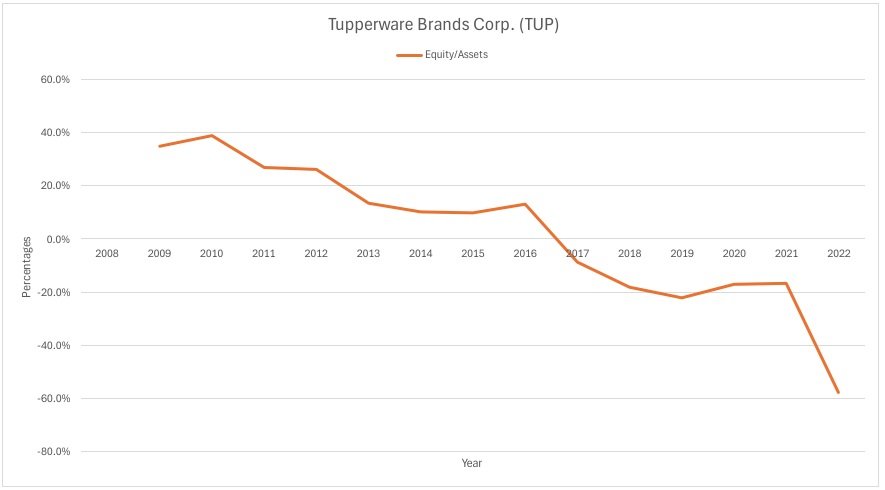

A second serious problem was the rapid growth of financial leverage, or debt burden. Generous dividend payments and stock buybacks were largely financed with borrowed money. The company’s balance sheet became increasingly risky—for example, by 2015, Tupperware’s debt-to-equity ratio was about 4.8. Such a high debt burden means that the company was overly dependent on borrowed funds and was vulnerable to any deterioration in the business environment. Although this did not yet seem like a crisis during the boom years, these indicators provided a clear early warning that Tupperware’s existing success model might be falling behind the times.

At the same time, fundamental changes were taking place in the market. Consumer purchasing preferences were increasingly moving towards e-commerce, reducing the attractiveness of home sales parties. Competition in the storage container market intensified—new competitors entered the market, and innovation in plastic products was no longer limited to Tupperware. Tupperware’s decades-long successful direct sales model began to look outdated. It is important to note that even in the late 2010s, Tupperware still relied predominantly on its historical sales channel: in 2023, about 90% of the company’s revenue still came from the direct sales network. The financial peak of 2013 was also a turning point, from which former strengths began to turn into weaknesses.

The Decline: Fall and Bankruptcy

After 2013, a long and painful decline began for Tupperware. It did not happen overnight or due to a single event but developed from the interaction of several factors. On one hand, the market environment changed—consumer buying behavior and the competitive landscape—and on the other, the company was unable to adapt to these changes quickly enough. The result was strategic stagnation, reflected in increasingly weakening economic results.

The company’s revenue began to decline quietly after 2013, and the fall later accelerated. While revenue in 2013 was $2.67 billion, by 2018, sales had already decreased noticeably, and by 2022, had fallen to $1.3 billion—more than 50% below the peak. The stock price reflected the company’s decline even more dramatically. After reaching its peak in 2013, Tupperware’s stock began to gradually fall. In 2019, the fall accelerated—in that year alone, the stock lost approximately 73% of its value as the company’s economic indicators deteriorated and investors lost faith in the firm’s ability to turn around.

In 2020, the global economy was hit by the COVID-19 pandemic, which caused a short-term rise in Tupperware’s stock: there was an increase in demand for food storage containers, and Tupperware’s stock unexpectedly grew by nearly 280% in 2020. The rise in stock price was driven by investor speculation—they hoped to profit from the pandemic. However, it soon became clear that this effect was temporary; as the world began to reopen, demand normalized, and Tupperware’s fundamental problems remained, causing the stock to decline again.

Financially, the company found itself in an increasingly difficult situation. The large debt load and declining sales led to Tupperware’s equity turning negative—liabilities exceeded the value of assets. With each subsequent quarter, an ever-larger portion of business income was spent on paying interest rather than developing the business. In other words, debt became more of a burden for the company than an engine for growth. Although management continued to pay dividends for a while longer (even as the dividend yield rose to unnaturally high levels due to the fall in stock price) and tried to instill optimism in investors, it was clear that the existing strategy was not sustainable. This was a classic dividend trap scenario—the high dividend yield did not stem from the strength of the business but from the collapse of the stock price, which often precedes a company’s demise.

By 2023, Tupperware had reached a critical state. The company’s sales continued to decline in all regions, including the previously strong Asian markets. The sales network shrank as fewer and fewer independent consultants found the motivation to operate in conditions of declining demand. In April 2023, Tupperware warned the public that the firm’s sustainability was in doubt—hinting at the possibility that it would be unable to continue business operations without additional capital.

Finally, in September 2024, Tupperware was forced to file for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection in the U.S., officially admitting its insolvency. This marked a sad but inevitable end as a public company for a business that had operated for over 75 years.

Strategic Lessons

The story of Tupperware’s rise and fall offers several important lessons that can be generalized more broadly in business and strategy:

- Financial indicators don’t lie (early warnings) – Major changes in a company’s trajectory are often predictable if one reads the financial statements carefully. Tupperware’s collapse was not a sudden shock but a years-long process that could have been foreseen: after 2013, the downward trend in revenue and growing financial leverage were clearly evident in public reports. It is important for investors and managers to monitor such trends early and ask uncomfortable questions before it is too late. The numbers reflect reality—when sales decrease and debts grow, these signals must not be ignored.

- The need to adapt to market changes – A successful business model in one era can become ineffective in another. The Tupperware case highlights that a company must continuously update its strategy according to consumer behavior and market developments. Tupperware relied on direct sales for decades, even as consumers moved to physical and online stores—in 2023, ~90% of sales still came from in-home sales channels. This inability to be flexible with channels accelerated the decline. The lesson: companies must keep pace with the evolving market and technology, whether it’s adopting e-commerce, new marketing methods, or appealing to a younger target audience. If the world around you changes, but you don’t, it is very difficult to survive—this can be seen directly from the Tupperware story.

- The danger of the dividend trap – A high dividend yield can prove to be an illusory gift. Tupperware’s stock dividend yield rose to double-digit percentages (over 10%) at one point due to the stock’s decline, which might have seemed attractive on the surface. In reality, it was a sign of Tupperware’s fragility—the high yield came from the sharp fall in the stock price, which preceded the suspension of dividends and the company’s insolvency. Investors should learn from this that an unreasonably high dividend yield is often a warning signal, not a risk-free source of income.

- The balance between debt and capital use – The decision by Tupperware’s management to finance stock buybacks and dividends with large amounts of borrowed money was a strategic mistake. Debt is like a double-edged sword: in good times, it amplifies returns, but in bad times, it becomes a burden that can knock the company out of the game. Tupperware borrowed aggressively but used the borrowed money incorrectly—instead of strengthening the business (e.g., investing in new sales channels or products), they bought back their own shares, artificially boosting profit metrics. The lesson: a company’s management must maintain a balance between returning value to shareholders and reinvesting in the company. Excessive financial leverage combined with an aggressive “buyout” of equity can leave a firm without a buffer in difficult times. Tupperware was ultimately left with no “breathing room”—when sales fell, there were no longer financial resources to implement a turnaround strategy because the resources had previously been distributed as dividends, and debt obligations still had to be serviced.